FOUR LONDON HOSPITALS

THE INDEPENDENT - December 7th 1918

BY HAMILTON HOLT

My first realisation of what Thomas Jefferson meant when he called war 'the greatest scourge of mankind' came to mind when I visited four of England's greatest hospitals for the wounded. These hospitals were SIDCUP, where living tissue if grafted onto men's faces to make new noses, ears and mouths; WANDSWORTH, where facial masks are designed to cover eyeless sockets and shot-away cheeks and jaws; ROEHAMPTON, where new arms and legs are manufactured and ST DUNSTAN'S where the blind are cared for and taught that even the most terribly handicapped life is worth living. These hospitals show England at her best and each marks a marvellous advance in the science and the art of healing.

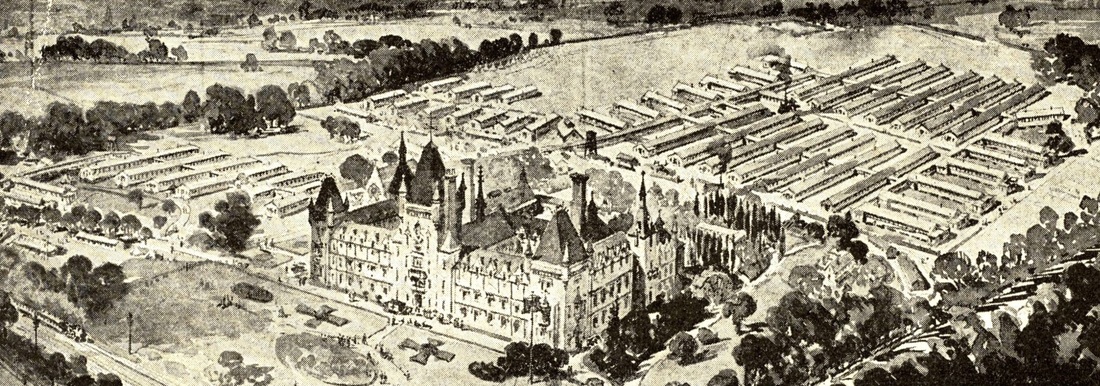

SIDCUP hospital lies in the open country a few minutes run by train beyond the suburbs of London. It was originally an old medieval brick manor house situated in a park filled with those ancient gnarled oak trees so familiar in Victorian etchings. It has now been given for these poor fellows who's faces have been mutilated beyond recognition by the 'Kultur'. Here they are taken in hand and truly marvellous results have been obtained. The face is the mirror of the mind, the medium thru which the soul finds expression but the Germans have transformed the most attractive features into something diabolical. An eye, maybe, is missing and in its place is a hideous socket with a bloodshot rim. Mobile lips on which smiles were wont to play are now all askew. The mouth maybe nothing but a formless cavity without a tooth, or more frightful yet, a jagged slit stretching from chin to forehead. Such facial wounds are the most horrible outcome of modern warfare. They are repulsive to everyone who's sees them and to this who have to bear such disfigurements they must be appalling.

When Dr Carrel made his famous discovery that cells taken form the human body are capable under certain conditions of reproducing themselves indefinitely, he perhaps did not fully realise the practical application of his discovery. It remained for a group of young surgeons in London to apply his principles to the human wreckage of the war and thus save from suicide thousands of men who would have preferred death to returning as objects of loathing to their family and friends.

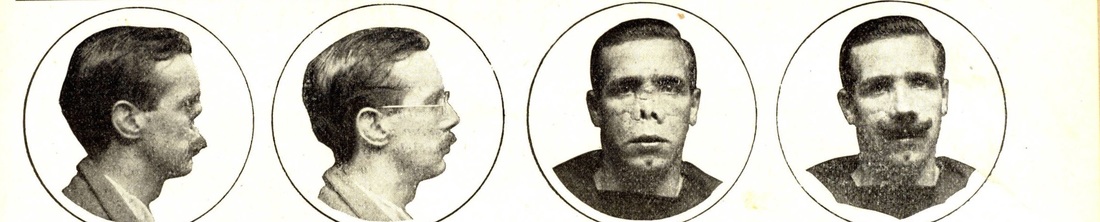

The surgeon in chief of the hospital showed us about. But with the usual British modesty, he made me promise I would not mention his name in connection with anything I might write about his institution. (Very likely to be Sir Harold Gillies). He first took us into the room in which were hung on the four walls plaster casts of mens faces, before and after treatment. He explained the surgical process usually employed in restoring facial mutilations. Suppose a man had his face so crushed that he has only a hole where his nose ought to be. The problem is to create a new living nose.The doctors will first procure an old picture to learn how the patient used to look. This will be the guide toward which all attempts at restoration will be made. The patient will then be put under ether and a piece of rib or shin bone will be taken and inserted into a slit in his forehead, which will then be sewn up. After the skin has grown over the bone and the bone has attached itself to ligaments, another operation is performed by which the bone is turned over on its lower axis and brought down to serve as the basis of the nose. Slits are cut into the skin on the cheeks on either side of the nose and on the upper lip. The flaps of skin thus released are brought over the nose and grafted on the gristle. After this is healed the flesh is massaged and trimmed until finally the man has a Greek or Roman nose perhaps better than his original organ.

We next made a tour of inspection of the wards, where we saw the men in all the various stages of treatment. The faces of some were almost too revolting look at. Others were just on the point of being sent home cured, with faces almost as good as new. We talked to many of the men and tho they said the treatment seemed unending and was very painful, yet they were all most happy with the results. I was told that surgeons from all the Allied nations have made pilgrimage to this hospital to learn the newest methods of grafting live flesh on old foundations and no doubt England's great pioneer work in this branch of surgery will soon be available for use throughout the world.

After the at the manor house, a WAAC who turned out to be the wife of the chief anaesthetician, drove us to the train in high powered car.

When we landed at Charing Cross Station in London just half an hour later, a hospital train was just pulling in, bringing the English wounded direct from the Flanders front, where the great German drive was still at its fiercest. There must have been fifty khaki coloured Red Cross automobiles drawn up under the great dome of the station waiting for the boys who had been trying to stem the German tide. A cordon of policemen was holding the crowd back. The driveway from the entrance to the station was flanked by two lines of spectators waiting to see the wounded carried out. It was about six in the evening and the crowd was composed mainly of shop girls and widows in mourning on their way home after a days work. Two slatternly women wearing mens straw hats were walking up and down selling crocuses to the thong and almost everyone bought one. I noticed a couple of bright eyed little wizened old ladies, each with handful of cigarets and a neighbour told me these same women met all the incoming trains of wounded, for the thing wounded soldier loves next to a word from home is a cigarets.

SIDCUP hospital lies in the open country a few minutes run by train beyond the suburbs of London. It was originally an old medieval brick manor house situated in a park filled with those ancient gnarled oak trees so familiar in Victorian etchings. It has now been given for these poor fellows who's faces have been mutilated beyond recognition by the 'Kultur'. Here they are taken in hand and truly marvellous results have been obtained. The face is the mirror of the mind, the medium thru which the soul finds expression but the Germans have transformed the most attractive features into something diabolical. An eye, maybe, is missing and in its place is a hideous socket with a bloodshot rim. Mobile lips on which smiles were wont to play are now all askew. The mouth maybe nothing but a formless cavity without a tooth, or more frightful yet, a jagged slit stretching from chin to forehead. Such facial wounds are the most horrible outcome of modern warfare. They are repulsive to everyone who's sees them and to this who have to bear such disfigurements they must be appalling.

When Dr Carrel made his famous discovery that cells taken form the human body are capable under certain conditions of reproducing themselves indefinitely, he perhaps did not fully realise the practical application of his discovery. It remained for a group of young surgeons in London to apply his principles to the human wreckage of the war and thus save from suicide thousands of men who would have preferred death to returning as objects of loathing to their family and friends.

The surgeon in chief of the hospital showed us about. But with the usual British modesty, he made me promise I would not mention his name in connection with anything I might write about his institution. (Very likely to be Sir Harold Gillies). He first took us into the room in which were hung on the four walls plaster casts of mens faces, before and after treatment. He explained the surgical process usually employed in restoring facial mutilations. Suppose a man had his face so crushed that he has only a hole where his nose ought to be. The problem is to create a new living nose.The doctors will first procure an old picture to learn how the patient used to look. This will be the guide toward which all attempts at restoration will be made. The patient will then be put under ether and a piece of rib or shin bone will be taken and inserted into a slit in his forehead, which will then be sewn up. After the skin has grown over the bone and the bone has attached itself to ligaments, another operation is performed by which the bone is turned over on its lower axis and brought down to serve as the basis of the nose. Slits are cut into the skin on the cheeks on either side of the nose and on the upper lip. The flaps of skin thus released are brought over the nose and grafted on the gristle. After this is healed the flesh is massaged and trimmed until finally the man has a Greek or Roman nose perhaps better than his original organ.

We next made a tour of inspection of the wards, where we saw the men in all the various stages of treatment. The faces of some were almost too revolting look at. Others were just on the point of being sent home cured, with faces almost as good as new. We talked to many of the men and tho they said the treatment seemed unending and was very painful, yet they were all most happy with the results. I was told that surgeons from all the Allied nations have made pilgrimage to this hospital to learn the newest methods of grafting live flesh on old foundations and no doubt England's great pioneer work in this branch of surgery will soon be available for use throughout the world.

After the at the manor house, a WAAC who turned out to be the wife of the chief anaesthetician, drove us to the train in high powered car.

When we landed at Charing Cross Station in London just half an hour later, a hospital train was just pulling in, bringing the English wounded direct from the Flanders front, where the great German drive was still at its fiercest. There must have been fifty khaki coloured Red Cross automobiles drawn up under the great dome of the station waiting for the boys who had been trying to stem the German tide. A cordon of policemen was holding the crowd back. The driveway from the entrance to the station was flanked by two lines of spectators waiting to see the wounded carried out. It was about six in the evening and the crowd was composed mainly of shop girls and widows in mourning on their way home after a days work. Two slatternly women wearing mens straw hats were walking up and down selling crocuses to the thong and almost everyone bought one. I noticed a couple of bright eyed little wizened old ladies, each with handful of cigarets and a neighbour told me these same women met all the incoming trains of wounded, for the thing wounded soldier loves next to a word from home is a cigarets.

In a few minutes the stretcher bearers had filled the first ambulance and it started down the lane of drab women. First a murmur and then a sigh rose from the spectators. As the car passed along, the crowd rushed out and through crocuses and cigarets in behind.

Each ambulance had four cots in it, in each of which lay a wounded soldier, while in the aisle between the cots crouched a trained nurse. The eyes of most of the crowd glistened and many are weeping and I could hear such murmurs as "poor boys" "the brave fellows" etc as they passed along. But if the bystanders were deeply moved, not so the boys. Most of them waved their hands or smiled and the flowers rained down upon them, ho I noticed two or three whose white lips quavered tho their eyes still faintly smiled their gratitude for being home in Blighty again. The crowd stayed until the fifty ambulances had passed each one pelted with flowers. Then it quickly dispersed and the smoky station went on again about it normal business.

The second hospital we visited was the General Hospital at Wandsworth where the new art of plastic surgery is practised. Most of the patients were officers. The genial colonel in charge (very likely Col H E Bruce Porter) Before the war the hospital was a famous old schoolhouse but it has now been converted into one of England's greatest medical institutions. The Colonel told me that when the war began he called a large number of the leading English painters and sculptors and said to the in effect "Now you painters, quit painting Lady Guinevere and peaceful vine clad thatched cottages and you sculptors, stop fashioning marble bust of Venus and Apollo; but all of you while the war lasts devote your talents to remodelling your fellow countrymen" So when a wounded soldier was received at the hospital with an eye or part of a cheek gone, the sculptor would take plaster cast of the mutilated side of the face and then with their of a pre war photograph, casts and measurements of the uninjured side. would fashion a new model to fit the hollow and when his job was done the painter would come and paint the flesh tints upon it. I have seen men with artificial jaws that ten feet away could not be distinguished from the real jaws. I have seen soldier with an artificial eye and cheek that he could put on when walking down the street and take out when he got home. No one would recognise it as false unless his attention was called to it.

Francis Derwent Wood was the artist who has been chiefly responsible for making these plaster casts. Before the war he was a painter at the Royal Academy where he had may pictures on exhibition. In 1915 he enlisted a private in the British army, but was detained to this hospital, where he speedily received recognition and was eventually put in a splint department where he developed the art of plastic surgery to its present point of perfection. We visited his office which was a moulder's workshop, studio and consulting room in one. On the walls were to be seen a strange collection of facial mask and records in plaster and photography. I hereby reproduce some of the pictures which he gave me. I noticed artificial ears as flexible looking and pink as tho they were made of flesh and blood, noses in part or in their entirity with the cheeks added and eyes that looked over the fake spectacles as naturally as to they are real organs of sight.

The process of making the artificial masks is roughly as follows: First the face is smeared with oil and vaseline and the wound cavity is filled up with dressing ad cotton wool. This preparation is then covered over with gold beater's skin and the nostrils filled with cotton wool, in order that the plaster will not stick to the face. The plastic surgeon is now ready to begin his work. His one desire is to restore the features and make them natural. He first puts the plaster on the face. After the mould has dried is removed and placed on one side to be thoroughly hardened before the next step, with French chalk on its inner surface. The Captain Wood reconstructs the destroyed features from the model taken from the negative of this cast. Everything depends finally on the efficiency of the various arrangements to the comfort of the patient. After the mask is completed a thin covering of cream coloured spirit enamel is put on as the best basis for the painting. The eyebrows are are now painted with a brush, but the eyelashes are made with thin metallic foil and cut fine with scissors.The restoration of such faces has been a matter of special study for three years in England and is the triumph of surgery in skilful and experienced hands. So fine indeed is the work that the most frightful face can be made to look natural except when one is very close to them.

I was agreeably pleased to see how cheerful, comfortable and homelike the ward rooms were for the convalescent officers. While I do not especially admire the English nurses costume with its enormous starched white headdress, everything else seemed more attractive than anything I saw subsequently in the French or American Hospitals. I was especially impressed with the red curtains at the windows and the red blankets on the beds in all the room and the sky-blue convalescent uniform that the patients wore. It gave the whole place a very warm, colourful and cheery atmosphere.

Queen Mary's Auxiliary Hospital at Roehampton was the third hospital we visited. It is under the command of General McLeod. "Hope Welcomes All Who Enter Here" is the motto over the doorway. It is indeed necessary to bring such hope to the disabled men who come here armless and legless. These men are not only given new limbs but are taught some useful occupation while they are in the institution.

The hospital does not take men from the moment they are wounded but only after the stumps of the arms and legs have healed up and are ready to have the artificial limbs put upon them.

The commandant first conducted us to where a man with an artificial arm was spading up garden. As far as I could see he could shovel earth over his shoulder as as any digger whole armed. The whole of his right arm had been amputated but his artificial arm was moved by straps attached to his shoulders. He had unscrewed his artificial hand at the wrist and the spade was attached to a hook at the stump.

We next went into the hut where artificial legs were manufactured. These are made from light seasoned willow and of course are hollow, with a genuine laced up boot at the bottom. When only one leg is gone there is no difficulty making a new one which will serve was well as the old. The difficultly comes when both legs are gone, especially if they have been amputated near the hip. In this case the two new artificial legs are usually made shorter by four or five inches than the old ones. This is because the nearer the ground one is the easier it is to balance. The patient however, in this case has to be taught to walk all over again. After the legs are first put on he propels himself between two parallel bars balancing and guiding himself with his hands. It is very hard work at first and I noticed the men had to stop at frequent intervals to rest and wine the moisture from their foreheads. I met one fellow with both legs amputated who had learned his loss so well that he could not only walk but could run and jump. I saw him take a running start along the hallway and jump out of a side door and into the garden four feet below. The jolt landing did not seem to discompose him at all.

All the artificial legs have joints at the knee, ankle and toe etc. Of course as a patient walks along his legs tend to remain stiff at the knee. Otherwise the leg might double up. When he wants to sit down he pushes a button at the thigh and the knee bends. A man with two complete artificial legs usually has to carry a cane but if his legs have been cut off at the knee he can walk almost as well as ever. The armless and legless men are all taught trades and have no difficulty in getting jobs. I addition to whatever a soldier may get at his trade the Government gives ham a pension of 27s 6d a week.

The hospital has a capacity for 900 patients and when I was there and when I was there 700 were undergoing treatment. Already 14,000 have graduated from the institution. No Americans had yet been sent to this hospital but the commandant said he expected them shortly. About forty percent of the men return to their old trades. The Government gives them complete training for at least six months in electricity, carpentry, shorthand, typewriting or book keeping.

The colonel said it was really an inspiration to work with these men. It was not a matter of money with them, for they are assured of their pensions for life. But they are determined to make the most of their opportunities and that spirit overcomes all handicaps.

The saddest sight I saw in England, perhaps the saddest sight I saw in Europe, was St Dunstan's Hospital, where 900 groping men were living- men who would never see the light of the sun for the rest of their lives. St Dunstan's, Regent Park, was once the home of the old reprobate Marquis of Steyne, the chief villain in Thackeray's 'Vanity Fair'. I recent years it has been the home of the American financier Otto Kahn. But when the war broke out Mr Kahn gave it to a distinguished committee under the chairmanship of Sir Arthur Pierson, the well known blind publisher. As I said, St Dunstan's was the saddest sight I saw in England, but it was only sad to the visitor, for I can truly say that I have never seen such real happiness in my life as was exhibited by the inmates of this peaceful homelike hospital. Everywhere was joyfulness, cheerfulness and bright smiles. In most of the rooms I found them singing at their work. Each patient has individual instruction and it warmed one's heart to see some good samaritan English girl teaching an eager soldier how to make daylight of his darkness. Down the middle of each room I noticed strips of oilcloth so that the man could walk by the feel of their feet. When they have to traverse some difficult place - say from one hut to another -a railing is put up so that they can guide themselves by the touch of the hand. I went into the assembly hall where the plays and musicals are given. The plays are just the same as would be presented in any theatre except that it would not be necessary to have scenery, property or costumes. We looked into a room where a nurse was teaching dozen men the art of massaging, an art at which they become most adept. When we went thru the huts where they were learning basket weaving, carpentry, shoemaking, cabinet making and loom weaving. Ina another room we saw them being taught Braille. In an out hut we found them learning how to raise chickens and rabbits.

In the carpentry department a blind man had become so proficient that he was made foreman. He told me that they seldom allowed a man to take up his old trade, for a man had very fixed ideas on that subject and is not therefore teachable. They almost invariably start him on something far removed from his old occupation so that he can have no grounds for arguing about the way he is being taught. But wherever we went in that old historic country place we could feel its splendid spirit. No wonder it has been called 'The happiest House in London'.

Most of the blind had broken noses or smashed faces but as they will never see how they lookout is not thought necessary to ask then to undergo the sever treatment such as they would receive in the Sidcup or Wandsworth Hospitals simply to make them more sightly to their friends and relations. I am told that many women take compassion on these man and marry them, especially women whose lovers or husbands have been killed at the front.

For purposes of admission no man is considered eligible unless his sight is considered so injured that he is incapable of earning an independent existence. There are many therefore who can distinguish light, tho a large majority are absolutely blind. It is said that it is far better for man to go blind young than to use his sight after middle age. Youth's buoyancy and powers of repair, mental and physical and its inherent faculty of living in and for the present make it more possible for blinded youth to start life over than for the middle aged.

I was told that one of the most important points in the training at St Dunstan's is the teaching of independence. Blind men are instinctively timid and dependent. The greatest pains therefore are taken to teach them to shift for themselves.

Whatever occupation the men train for practically all of them learn to master Braille and the typewriter. Very man is given a typewriter as his own personal possession when he has passed the writing test imposed. The reason that typewriting is taught - except to this who have learned shorthand before- is because the hand writing of a blind man very soon deteriorates almost to the point of illegibility.

The curriculum is divided onto two class room periods, two and a half hours in the morning and two hours in the afternoon. No matter how badly a man is afflicted something can always be found for him to do. I was told of the case of one who had not only lost both his eyes but both arms and legs. He was taught to lecture for the hospital. He was sent all over the United Kingdom and was said to be wonderful money getter for the institution.

The men are taught to play as well as work. They row,swim,and have running races and contests of war. Even drill is regularly practised. There are two faces every week, one a lesson and one a regular ball, to which, each one may invite a lady friend. Debating is also very popular.

AS I have said at the beginning of this article nothing is more credible to the English Humanitarian spirit than her hospitals. While I was in London I noticed the following advertisement in the Times: "Blood transfusion. Only chance of life for soldier's orphan. Immediate offers from healthy adults to Child Welfare Inquiry Office, 845 Salisbury House, E.D. 2 telephone : London Wall 5169". I learned that may hundreds of offers were made in response to this advertisement and volunteers came forth from every class, including officers, soldiers, sailors and wage earning girls. Even wounded soldiers have gone out of their way to say that they were perfectly fit and would like to help a soldier's child. A boy of seventeen offered his blood "for the kid because his father died for me" and a soldier's wife with her little children around her said "I am pretty strong and I'd like to do it just as if it were one of my own." This is the spirit of England toward those who suffer.

In conclusion may I assure American fathers and mothers that if their wounded boys have been sent to an English hospital they can rest absolutely certain that everything that medical science can do will be done for them and that England will treat them just as tenderly as her own.

And further, any American boy who visits England on his leave of absence will find England as truly Blighty for him as it is for the Tommies. The English people have already many organisations to welcome him and they will take the best of care of him whether in illness or health. We Americans often get the impression that the English are a cold and self sufficient people, but the real explanation of their reserve is that they are shy and have an almost abnormal fear that other people may think them obtrusive, There is no warmer heart at bottom that the English heart and any of our boys who have been cared for in English hospitals or welcomed in English homes will never misunderstand the magnanimity and generous hearts of our cousins across the sea.

Each ambulance had four cots in it, in each of which lay a wounded soldier, while in the aisle between the cots crouched a trained nurse. The eyes of most of the crowd glistened and many are weeping and I could hear such murmurs as "poor boys" "the brave fellows" etc as they passed along. But if the bystanders were deeply moved, not so the boys. Most of them waved their hands or smiled and the flowers rained down upon them, ho I noticed two or three whose white lips quavered tho their eyes still faintly smiled their gratitude for being home in Blighty again. The crowd stayed until the fifty ambulances had passed each one pelted with flowers. Then it quickly dispersed and the smoky station went on again about it normal business.

The second hospital we visited was the General Hospital at Wandsworth where the new art of plastic surgery is practised. Most of the patients were officers. The genial colonel in charge (very likely Col H E Bruce Porter) Before the war the hospital was a famous old schoolhouse but it has now been converted into one of England's greatest medical institutions. The Colonel told me that when the war began he called a large number of the leading English painters and sculptors and said to the in effect "Now you painters, quit painting Lady Guinevere and peaceful vine clad thatched cottages and you sculptors, stop fashioning marble bust of Venus and Apollo; but all of you while the war lasts devote your talents to remodelling your fellow countrymen" So when a wounded soldier was received at the hospital with an eye or part of a cheek gone, the sculptor would take plaster cast of the mutilated side of the face and then with their of a pre war photograph, casts and measurements of the uninjured side. would fashion a new model to fit the hollow and when his job was done the painter would come and paint the flesh tints upon it. I have seen men with artificial jaws that ten feet away could not be distinguished from the real jaws. I have seen soldier with an artificial eye and cheek that he could put on when walking down the street and take out when he got home. No one would recognise it as false unless his attention was called to it.

Francis Derwent Wood was the artist who has been chiefly responsible for making these plaster casts. Before the war he was a painter at the Royal Academy where he had may pictures on exhibition. In 1915 he enlisted a private in the British army, but was detained to this hospital, where he speedily received recognition and was eventually put in a splint department where he developed the art of plastic surgery to its present point of perfection. We visited his office which was a moulder's workshop, studio and consulting room in one. On the walls were to be seen a strange collection of facial mask and records in plaster and photography. I hereby reproduce some of the pictures which he gave me. I noticed artificial ears as flexible looking and pink as tho they were made of flesh and blood, noses in part or in their entirity with the cheeks added and eyes that looked over the fake spectacles as naturally as to they are real organs of sight.

The process of making the artificial masks is roughly as follows: First the face is smeared with oil and vaseline and the wound cavity is filled up with dressing ad cotton wool. This preparation is then covered over with gold beater's skin and the nostrils filled with cotton wool, in order that the plaster will not stick to the face. The plastic surgeon is now ready to begin his work. His one desire is to restore the features and make them natural. He first puts the plaster on the face. After the mould has dried is removed and placed on one side to be thoroughly hardened before the next step, with French chalk on its inner surface. The Captain Wood reconstructs the destroyed features from the model taken from the negative of this cast. Everything depends finally on the efficiency of the various arrangements to the comfort of the patient. After the mask is completed a thin covering of cream coloured spirit enamel is put on as the best basis for the painting. The eyebrows are are now painted with a brush, but the eyelashes are made with thin metallic foil and cut fine with scissors.The restoration of such faces has been a matter of special study for three years in England and is the triumph of surgery in skilful and experienced hands. So fine indeed is the work that the most frightful face can be made to look natural except when one is very close to them.

I was agreeably pleased to see how cheerful, comfortable and homelike the ward rooms were for the convalescent officers. While I do not especially admire the English nurses costume with its enormous starched white headdress, everything else seemed more attractive than anything I saw subsequently in the French or American Hospitals. I was especially impressed with the red curtains at the windows and the red blankets on the beds in all the room and the sky-blue convalescent uniform that the patients wore. It gave the whole place a very warm, colourful and cheery atmosphere.

Queen Mary's Auxiliary Hospital at Roehampton was the third hospital we visited. It is under the command of General McLeod. "Hope Welcomes All Who Enter Here" is the motto over the doorway. It is indeed necessary to bring such hope to the disabled men who come here armless and legless. These men are not only given new limbs but are taught some useful occupation while they are in the institution.

The hospital does not take men from the moment they are wounded but only after the stumps of the arms and legs have healed up and are ready to have the artificial limbs put upon them.

The commandant first conducted us to where a man with an artificial arm was spading up garden. As far as I could see he could shovel earth over his shoulder as as any digger whole armed. The whole of his right arm had been amputated but his artificial arm was moved by straps attached to his shoulders. He had unscrewed his artificial hand at the wrist and the spade was attached to a hook at the stump.

We next went into the hut where artificial legs were manufactured. These are made from light seasoned willow and of course are hollow, with a genuine laced up boot at the bottom. When only one leg is gone there is no difficulty making a new one which will serve was well as the old. The difficultly comes when both legs are gone, especially if they have been amputated near the hip. In this case the two new artificial legs are usually made shorter by four or five inches than the old ones. This is because the nearer the ground one is the easier it is to balance. The patient however, in this case has to be taught to walk all over again. After the legs are first put on he propels himself between two parallel bars balancing and guiding himself with his hands. It is very hard work at first and I noticed the men had to stop at frequent intervals to rest and wine the moisture from their foreheads. I met one fellow with both legs amputated who had learned his loss so well that he could not only walk but could run and jump. I saw him take a running start along the hallway and jump out of a side door and into the garden four feet below. The jolt landing did not seem to discompose him at all.

All the artificial legs have joints at the knee, ankle and toe etc. Of course as a patient walks along his legs tend to remain stiff at the knee. Otherwise the leg might double up. When he wants to sit down he pushes a button at the thigh and the knee bends. A man with two complete artificial legs usually has to carry a cane but if his legs have been cut off at the knee he can walk almost as well as ever. The armless and legless men are all taught trades and have no difficulty in getting jobs. I addition to whatever a soldier may get at his trade the Government gives ham a pension of 27s 6d a week.

The hospital has a capacity for 900 patients and when I was there and when I was there 700 were undergoing treatment. Already 14,000 have graduated from the institution. No Americans had yet been sent to this hospital but the commandant said he expected them shortly. About forty percent of the men return to their old trades. The Government gives them complete training for at least six months in electricity, carpentry, shorthand, typewriting or book keeping.

The colonel said it was really an inspiration to work with these men. It was not a matter of money with them, for they are assured of their pensions for life. But they are determined to make the most of their opportunities and that spirit overcomes all handicaps.

The saddest sight I saw in England, perhaps the saddest sight I saw in Europe, was St Dunstan's Hospital, where 900 groping men were living- men who would never see the light of the sun for the rest of their lives. St Dunstan's, Regent Park, was once the home of the old reprobate Marquis of Steyne, the chief villain in Thackeray's 'Vanity Fair'. I recent years it has been the home of the American financier Otto Kahn. But when the war broke out Mr Kahn gave it to a distinguished committee under the chairmanship of Sir Arthur Pierson, the well known blind publisher. As I said, St Dunstan's was the saddest sight I saw in England, but it was only sad to the visitor, for I can truly say that I have never seen such real happiness in my life as was exhibited by the inmates of this peaceful homelike hospital. Everywhere was joyfulness, cheerfulness and bright smiles. In most of the rooms I found them singing at their work. Each patient has individual instruction and it warmed one's heart to see some good samaritan English girl teaching an eager soldier how to make daylight of his darkness. Down the middle of each room I noticed strips of oilcloth so that the man could walk by the feel of their feet. When they have to traverse some difficult place - say from one hut to another -a railing is put up so that they can guide themselves by the touch of the hand. I went into the assembly hall where the plays and musicals are given. The plays are just the same as would be presented in any theatre except that it would not be necessary to have scenery, property or costumes. We looked into a room where a nurse was teaching dozen men the art of massaging, an art at which they become most adept. When we went thru the huts where they were learning basket weaving, carpentry, shoemaking, cabinet making and loom weaving. Ina another room we saw them being taught Braille. In an out hut we found them learning how to raise chickens and rabbits.

In the carpentry department a blind man had become so proficient that he was made foreman. He told me that they seldom allowed a man to take up his old trade, for a man had very fixed ideas on that subject and is not therefore teachable. They almost invariably start him on something far removed from his old occupation so that he can have no grounds for arguing about the way he is being taught. But wherever we went in that old historic country place we could feel its splendid spirit. No wonder it has been called 'The happiest House in London'.

Most of the blind had broken noses or smashed faces but as they will never see how they lookout is not thought necessary to ask then to undergo the sever treatment such as they would receive in the Sidcup or Wandsworth Hospitals simply to make them more sightly to their friends and relations. I am told that many women take compassion on these man and marry them, especially women whose lovers or husbands have been killed at the front.

For purposes of admission no man is considered eligible unless his sight is considered so injured that he is incapable of earning an independent existence. There are many therefore who can distinguish light, tho a large majority are absolutely blind. It is said that it is far better for man to go blind young than to use his sight after middle age. Youth's buoyancy and powers of repair, mental and physical and its inherent faculty of living in and for the present make it more possible for blinded youth to start life over than for the middle aged.

I was told that one of the most important points in the training at St Dunstan's is the teaching of independence. Blind men are instinctively timid and dependent. The greatest pains therefore are taken to teach them to shift for themselves.

Whatever occupation the men train for practically all of them learn to master Braille and the typewriter. Very man is given a typewriter as his own personal possession when he has passed the writing test imposed. The reason that typewriting is taught - except to this who have learned shorthand before- is because the hand writing of a blind man very soon deteriorates almost to the point of illegibility.

The curriculum is divided onto two class room periods, two and a half hours in the morning and two hours in the afternoon. No matter how badly a man is afflicted something can always be found for him to do. I was told of the case of one who had not only lost both his eyes but both arms and legs. He was taught to lecture for the hospital. He was sent all over the United Kingdom and was said to be wonderful money getter for the institution.

The men are taught to play as well as work. They row,swim,and have running races and contests of war. Even drill is regularly practised. There are two faces every week, one a lesson and one a regular ball, to which, each one may invite a lady friend. Debating is also very popular.

AS I have said at the beginning of this article nothing is more credible to the English Humanitarian spirit than her hospitals. While I was in London I noticed the following advertisement in the Times: "Blood transfusion. Only chance of life for soldier's orphan. Immediate offers from healthy adults to Child Welfare Inquiry Office, 845 Salisbury House, E.D. 2 telephone : London Wall 5169". I learned that may hundreds of offers were made in response to this advertisement and volunteers came forth from every class, including officers, soldiers, sailors and wage earning girls. Even wounded soldiers have gone out of their way to say that they were perfectly fit and would like to help a soldier's child. A boy of seventeen offered his blood "for the kid because his father died for me" and a soldier's wife with her little children around her said "I am pretty strong and I'd like to do it just as if it were one of my own." This is the spirit of England toward those who suffer.

In conclusion may I assure American fathers and mothers that if their wounded boys have been sent to an English hospital they can rest absolutely certain that everything that medical science can do will be done for them and that England will treat them just as tenderly as her own.

And further, any American boy who visits England on his leave of absence will find England as truly Blighty for him as it is for the Tommies. The English people have already many organisations to welcome him and they will take the best of care of him whether in illness or health. We Americans often get the impression that the English are a cold and self sufficient people, but the real explanation of their reserve is that they are shy and have an almost abnormal fear that other people may think them obtrusive, There is no warmer heart at bottom that the English heart and any of our boys who have been cared for in English hospitals or welcomed in English homes will never misunderstand the magnanimity and generous hearts of our cousins across the sea.